Lung / Bronchus Cancer

Lung cancer is one of the most common and serious types of cancer. More than 43,000 people are diagnosed with the condition every year in the UK.

There are usually no signs or symptoms in the early stages of lung cancer, but many people with the condition eventually develop symptoms including:

- a persistent cough

- coughing up blood

- persistent breathlessness

- unexplained tiredness and weight loss

- an ache or pain when breathing or coughing

Types of Lung Cancer

Cancer that begins in the lungs is called primary lung cancer. Cancer that spreads to the lungs from another place in the body is known as secondary lung cancer. This page is about primary lung cancer. There are two main forms of primary lung cancer. These are classified by the type of cells in which the cancer starts growing. They are:

- non-small-cell lung cancer – the most common form, accounting for around 80 to 85 out of 100 cases. It can be one of three types: squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma or large-cell carcinoma.

- small-cell lung cancer – a less common form that usually spreads faster than non-small-cell lung cancer.

Who's affected?

Lung cancer mainly affects older people. It's rare in people younger than 40.

More than 4 out of 10 people diagnosed with lung cancer in the UK are aged 75 and older.

Although people who have never smoked can develop lung cancer, smoking is the most common cause (accounting for more than 70 out of 100 cases).

This is because smoking involves regularly inhaling a number of different toxic substances

Treating Lung Cancer

Treatment depends on the type of mutation the cancer has, how far it's spread and how good your general health is. If the condition is diagnosed early and the cancerous cells are confined to a small area, surgery to remove the affected area of lung may be recommended.

If surgery is unsuitable due to your general health, radiotherapy to destroy the cancerous cells may be recommended instead.

If the cancer has spread too far for surgery or radiotherapy to be effective, chemotherapy is usually used.

There are also a number of medicines known as targeted therapies. They target a specific change in or around the cancer cells that is helping them to grow. Targeted therapies cannot cure lung cancer but they can slow its spread.

Outlook

Lung cancer does not usually cause noticeable symptoms until it's spread through the lungs or into other parts of the body. This means the outlook for the condition is not as good as many other types of cancer. About 2 in 5 people with the condition live for at least 1 year after they're diagnosed, and about 1 in 10 people live at least 10 years.

However, survival rates vary widely, depending on how far the cancer has spread at the time of diagnosis. Early diagnosis can make a big difference.

Symptoms Lung Cancer

There are usually no signs or symptoms of lung cancer in the early stages. Symptoms develop as the condition progresses.

The main symptoms of lung cancer include:

- a cough that does not go away after 3 weeks

- a long-standing cough that gets worse

- chest infections that keep coming back

- coughing up blood

- an ache or pain when breathing or coughing

- persistent breathlessness

- persistent tiredness or lack of energy

- loss of appetite or unexplained weight loss

Less common symptoms of lung cancer include:

- changes in the appearance of your fingers, such as becoming more curved or their ends becoming larger (this is known as finger clubbing)

- difficulty swallowing (dysphagia) or pain when swallowing

- wheezing

- a hoarse voice

- swelling of your face or neck

- persistent chest or shoulder pain

See a GP if you have any of the main symptoms of lung cancer or any of the less common symptoms.

Causes - Lung Cancer

Most cases of lung cancer are caused by smoking, although people who have never smoked can also develop the condition.

Smoking

Smoking cigarettes is the single biggest risk factor for lung cancer. It's responsible for more than 7 out of 10 cases.

Tobacco smoke contains more than 60 different toxic substances, which are known to be carcinogenic (cancer-producing).

If you smoke more than 25 cigarettes a day, you are 25 times more likely to get lung cancer than someone who does not smoke.

Frequent exposure to other people’s tobacco smoke (passive smoking) can also increase your risk of developing lung cancer.

While smoking cigarettes is the biggest risk factor, using other types of tobacco products can also increase your risk of developing lung cancer and other types of cancer, such as oesophageal cancer and mouth cancer.

These products include:

- cigars

- pipe tobacco

- snuff (a powdered form of tobacco)

- chewing tobacco

Smoking cannabis may also increase the risk of developing lung cancer. Most people who smoke cannabis mix it with tobacco. While they tend to smoke less tobacco than people who smoke regular cigarettes, they usually inhale more deeply and hold the smoke in their lungs for longer.

Radon

Radon is a natural radioactive gas that comes from tiny amounts of uranium present in all rocks and soils. It can sometimes be found in buildings.

If radon is breathed in, it can damage your lungs, particularly if you smoke. Radon gas causes a small number of lung cancer deaths in England.

Occupational exposure and pollution

Exposure to certain chemicals and substances which are used in several occupations and industries may increase your risk of developing lung cancer. These chemicals and substances include:

- arsenic

- asbestos

- beryllium

- cadmium

- coal and coke fumes

- silica

- nickel

Research has also found that frequently being exposed to diesel fumes over many years increases your risk of developing lung cancer.

Diagnosis

The GP will ask about your general health and your symptoms. They may examine you and ask you to breathe into a device called a spirometer, which measures how much air you breathe in and out.

You may be asked to have a blood test to rule out some of the possible causes of your symptoms, such as a chest infection.

Chest X-ray

A chest X-ray is usually the 1st test used to diagnose lung cancer. Most lung tumours appear on X-rays as a white-grey mass. However, chest X-rays cannot give a definitive diagnosis because they often cannot distinguish between cancer and other conditions, such as a lung abscess (a collection of pus that forms in the lungs).

If a chest X-ray suggests you may have lung cancer, you should be referred to a specialist in chest conditions.

A specialist can arrange more tests to investigate whether you have lung cancer and, if you do, what type it is and how much it's spread

CT scan

A CT scan is usually the next test you'll have after a chest X-ray.

A CT scan uses X-rays and a computer to create detailed images of the inside of your body.

Before having a CT scan, you'll be given an injection containing a special dye called a contrast medium, which helps to improve the quality of the images.

The scan is painless and takes 10 to 30 minutes.

PET-CT scan

You may have a PET-CT scan may be done if the results of a CT scan show you have cancer.

The PET-CT scan (which stands for positron emission tomography-computerised tomography) can show where there are active cancer cells. This can help with diagnosis and choosing the best treatment.

Before having a PET-CT scan, you'll be injected with a slightly radioactive material. You'll be asked to lie down on a table, which slides into the PET scanner.

The scan is painless and takes 30 to 60 minutes.

Bronchoscopy and Biopsy

If a CT scan shows there might be cancer in the central part of your chest, you may be offered a bronchoscopy. A bronchoscopy is a procedure that allows a doctor to see the inside of your airways and remove a small sample of cells (biopsy).

During a bronchoscopy, a thin tube with a camera at the end, called a bronchoscope, is passed through your mouth or nose, down your throat and into your airways.

The procedure may be uncomfortable, so you'll be offered a sedative before it starts, to help you relax, and a local anaesthetic to make your throat numb. The procedure takes around 30 to 40 minutes.

A newer procedure is called an endobronchial ultrasound scan (EBUS), which combines a bronchoscopy with an ultrasound scan.

Like a bronchoscopy, an EBUS allows a doctor to see the inside of your airways. However, the ultrasound probe on the end of the camera also allows the doctor to locate the lymph nodes in the centre of the chest so they can take a biopsy from them.

The procedure takes around 90 minutes.

Lymph nodes are part of a network of vessels and glands that spread throughout the body and work as part of your immune system.

A biopsy from a lymph node can show if cancerous cells are growing there and what type they are.

Thoracoscopy

A thoracoscopy is a procedure that allows a doctor to examine a particular area of your chest and take tissue and fluid samples. You're likely to need a general anaesthetic before having a thoracoscopy.

Two or three small cuts will be made in your chest to pass a tube (similar to a bronchoscope) into your chest.

A doctor uses the tube to look inside your chest and take tissue samples. The samples are then sent to a laboratory for testing.

After a thoracoscopy, you may need to stay in hospital overnight while any fluid in your lungs is drained.

Mediastinoscopy

A mediastinoscopy allows a doctor to examine the area between your lungs at the centre of your chest (mediastinum). For this test, you'll need to have a general anaesthetic and stay in hospital for a couple of days.

The doctor will make a small cut at the bottom of your neck so they can pass a thin tube into your chest. The tube has a camera at the end, which enables a doctor to see inside your chest.

They'll also be able to take samples of cells from your lymph nodes during the procedure. The lymph nodes are tested because they're usually the first place that lung cancer spreads to.

Percutaneous Needle Biopsy

During a percutaneous needle biopsy, a local anaesthetic is used to numb the skin.

A doctor then uses a CT scanner or ultrasound scanner to guide a needle through your skin into your lung to the site of a suspected tumour.

The needle is used to remove a small amount of tissue from a suspected tumour so it can be tested at a laboratory.

Risks of Biopsies

Like all medical procedures, a lung biopsy carries a small risk of complications, such as a pneumothorax. This is when air leaks out of the lung and into the space between your lungs and the chest wall. This can put pressure on the lung, causing it to collapse.

The clinician doing the biopsy will be aware of the potential risks involved. They should explain all the risks in detail before you agree to have the procedure. They will monitor you to check for symptoms of a pneumothorax, such as sudden shortness of breath.

If a pneumothorax does happen, it can be treated using a needle or tube to remove the excess air, allowing the lung to expand normally again.

Staging

Once tests have been completed, it should be possible for doctors to know what stage your cancer is, what this means for your treatment and whether it's possible to completely cure the cancer.

Non-small-cell lung cancer staging

Clinicians use a staging system for lung cancer called TNM, where:

- T describes the size of the tumour (cancerous tissue)

- N describes the spread of the cancer into lymph nodes

- M describes whether the cancer has spread to another area of the body such as the liver (metastasis).

Small-cell Lung Cancer

Small-cell lung cancer is less common than non-small-cell lung cancer. The cancerous cells are smaller in size than the cells that cause non-small-cell lung cancer.

Small-cell lung cancer only has 2 possible stages:

- limited disease – where the cancer is only in 1 lung and may be in nearby lymph nodes

- extensive disease – where the cancer has spread to the other lung, to lymph nodes that are further away, or to other parts of your body.

T

There are 4 main stages for T: T1 lung cancer means that the cancer is still inside the lung.

T1 is broken down into 3 sub-stages:

- T1a – the tumour is no wider than 1cm

- T1b – the tumour is between 1cm and 2cm wide

- T1c – the tumour is between 2cm and 3cm wide

T2 is used to describe 3 possibilities:

- the tumour is between 3cm and 5cm wide, or

- the tumour has spread into the main airway or the inner lining of the chest wall, or

- the lung has collapsed or is blocked due to inflammation

T3 is used to describe 3 possibilities:

- the tumour is between 5cm and 7cm wide, or

- there is more than 1 tumour in the lung lobe, or

- the tumour has spread into the chest wall, the phrenic nerve (a nerve close to the lungs), or the outer layer of the heart (pericardium)

T4 is used to describe a range of possibilities including:

- the tumour is wider than 7cm, or

- the tumour has spread into both sections of the lung (each lung is made up of 2 sections, known as lobes), or

- the tumour has spread into an area of the body near to the lung, such as the heart, the windpipe, the food pipe (oesophagus) or a major blood vessel

N

There are 3 main stages for N: N1 is used to describe cancerous cells in the lymph nodes located inside the lung or in the area where the lungs connect to the airway (the hilum).

N2 is used to describe 2 possibilities:

- there are cancerous cells in the lymph nodes located in the centre of the chest on the same side as the affected lung, or

- there are cancerous cells in the lymph nodes underneath the windpipe

N3 is used to describe 3 possibilities:

- there are cancerous cells in the lymph nodes located on the chest wall on the other side of the affected lung, or

- there are cancerous cells in the lymph nodes above the collar bone, or

- there are cancerous cells in the lymph nodes at the top of the lung

M

There are 2 main stages for M:

- M0 – the cancer has not spread outside the lung to another part of the body

- M1 – the cancer has spread outside the lung to another part of the body

Treatment

Treatment for lung cancer is managed by a team of specialists from different departments who work together to provide the best possible treatment. This team includes the health professionals required to make a diagnosis, to stage your cancer and to plan the best treatment. If you want to know more, ask your doctor or nurse about this.

The type of treatment you receive for lung cancer depends on several factors, including:

- the type of lung cancer you have (non-small-cell or small-cell mutations on the cancer)

- the size and position of the cancer

- how advanced your cancer is (the stage)

- your overall health

- Deciding what treatment is best for you can be difficult. Your cancer team will make recommendations, but the final decision will be yours.

The most common treatment options include surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy and immunotherapy. Depending on the type of cancer and the stage, you may receive a combination of these treatments.

Your suggested treatment plan depends on whether you have non-small-cell lung cancer or small-cell lung cancer.

Non-small-cell Lung Cancer

If you have non-small-cell lung cancer that's in only 1 of your lungs and you're in good general health, you'll probably have surgery to remove the cancerous cells. This may be followed by a course of chemotherapy to destroy any cancer cells that may have remained in your body.

If the cancer has not spread far but surgery is not possible (for example, because your general health means you have an increased risk of complications), you may be offered radiotherapy to destroy the cancerous cells. In some cases, this may be combined with chemotherapy (known as chemoradiotherapy).

If the cancer has spread too far for surgery or radiotherapy to be effective, chemotherapy and / or immunotherapy is usually recommended.

If the cancer starts to grow again after you have had chemotherapy treatment, another course of treatment may be recommended.

In some cases, if the cancer has a specific mutation, biological or targeted therapy may be recommended instead of chemotherapy, or after chemotherapy.

Biological therapies are medicines that control or stop the growth of cancer cells.

Small-cell Lung Cancer

Small-cell lung cancer is usually treated with chemotherapy, either on its own or in combination with radiotherapy or immunotherapy. This can help to prolong life and relieve symptoms.

Surgery is not usually used to treat this type of lung cancer. This is because the cancer has often already spread to other areas of the body by the time it's diagnosed.

However, if the cancer is found very early, surgery may be used. In these cases, chemotherapy or radiotherapy may be given after surgery to help reduce the risk of the cancer returning.

Surgery

There are 3 main types of lung cancer surgery:

- lobectomy – where 1 of the large parts of the lung (lobes) is removed. Your doctors will suggest this operation if the cancer is just in 1 section of 1 lung.

- pneumonectomy – where the entire lung is removed. This is used when the cancer is located in the middle of the lung or has spread throughout the lung.

- wedge resection or segmentectomy – where a small piece of the lung is removed. This procedure is only suitable for a small number of patients. It is only used if your doctors think your cancer is small and limited to one area of the lung. This is usually very early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer.

You may be concerned about being able to breathe if some or all of your lung is removed, but it's possible to breathe normally with 1 lung.

However, if you have breathing problems before the operation, it's likely these symptoms will continue after surgery.

Radiotherapy

Radiotherapy uses pulses of radiation to destroy cancer cells. There are a number of ways it can be used to treat lung cancer. An intensive course of radiotherapy, known as radical radiotherapy, may be used to treat non-small-cell lung cancer if you are not healthy enough for surgery.

For very small tumours, a special type of radiotherapy called stereotactic radiotherapy may be used instead of surgery.

Radiotherapy can also be used to control the symptoms, such as pain and coughing up blood, and to slow the spread of cancer when a cure is not possible (this is known as palliative radiotherapy).

A type of radiotherapy known as prophylactic cranial irradiation (PCI) is also sometimes used during the treatment of small-cell lung cancer.

PCI involves treating the whole brain with a low dose of radiation.

It's used as a preventative measure because there's a risk that small-cell lung cancer will spread to your brain.

Photodynamic Therapy

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) can be used to treat early-stage lung cancer when a person is unable or unwilling to have surgery. It can also be used to remove a tumour that's blocking the airways. Photodynamic therapy is done in 2 stages.

The next stage is done 24 to 72 hours later. A thin tube is guided to the site of the tumour and a laser is beamed through it.

The cancerous cells, which have become more sensitive to light, are destroyed by the laser beam.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy uses powerful cancer-killing medicine to treat cancer. There are several ways that chemotherapy can be used to treat lung cancer. For example, it can be: given before surgery to shrink a tumour, which can increase the chance of successful surgery (this is usually only done as part of a clinical trial)

- given after surgery to prevent the cancer returning

- used to relieve symptoms and slow the spread of cancer when a cure is not possible

- combined with radiotherapy

- Chemotherapy treatments are usually given in cycles.

A cycle involves taking chemotherapy medicine for several days, then having a break for a few weeks to let the therapy work and for your body to recover from the effects of the treatment.

The number of cycles you need will depend on the type and grade of lung cancer.

Most people need 4 to 6 cycles of treatment over 3 to 6 months.

You will see your doctor after these cycles have finished. If the cancer has improved, you may not need any more treatment.

If the cancer has not improved after these cycles, your doctor will tell you if you need a different type of chemotherapy. Alternatively, you may need maintenance chemotherapy to keep the cancer under control.

Chemotherapy for lung cancer involves taking a combination of different medicines.

The medicines are usually given through a drip into a vein (intravenously), or into a tube connected to one of the blood vessels in your chest

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy is a group of medicines that stimulate your immune system to target and kill cancer cells. It can be used on its own or combined with chemotherapy. Some of the immunotherapy medicines used to treat lung cancer are pembrolizumab and atezolizumab.

You might have immunotherapy through a plastic tube that goes into:

a large vein your chest (central line)

a vein in your arm (cannula)

It takes around 30 to 60 minutes to receive a dose, and you may need a dose every 2 to 4 weeks.

If the side effects are not too difficult to manage and the therapy is successful, immunotherapy can be taken for up to 2 years.

Common side effects of immunotherapy include:

- feeling tired or weak

- feeling and being sick

- diarrhoea

- loss of appetite

- pain in your joints or muscles

- shortness of breath

- changes to your skin, such as your skin becoming dry or itchy

Speak to your doctor or nurse for more information about side effects and how to manage them.

Some people may be given capsules or tablets to swallow instead.

Before you start chemotherapy, your doctor might prescribe you some vitamins and/or give you a vitamin injection.

Targeted Therapies

Targeted therapies (also known as biological therapies) are medicines designed to slow the spread of advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Targeted therapies are only suitable for people who have certain proteins in their cancerous cells.

Your doctor may request tests on cells removed from your lung (a biopsy) to see if these treatments are suitable for you.

Side-effects of targeted therapies include:

- flu-like symptoms such as chills, high temperature and muscle pain

- fatigue

- diarrhoea

- loss of appetite

- mouth ulcers

- feeling sick

Radiofrequency Ablation

Radiofrequency ablation may be used to treat non-small-cell lung cancer at an early stage. The doctor uses a CT scanner to guide a needle to the site of the tumour.

The needle is pressed into the tumour and radio waves are sent through the needle. These waves generate heat, which kills the cancer cells.

The most common complication of radiofrequency ablation is a pocket of air may become trapped between the inner and outer layer of your lung (pneumothorax).

This can be treated by placing a tube into the lungs to release the trapped air.

Cryotherapy

Cryotherapy can be used if the cancer starts to block your airways.

- This is known as endobronchial obstruction, and it can cause symptoms such as: breathing problems

- a cough

- coughing up blood

Cryotherapy is done in a similar way to internal radiotherapy, but instead of using a radioactive source, a device known as a cryoprobe is placed against the tumour.

The cryoprobe can generate very cold temperatures, which help to shrink the tumour.

Read more about lung cancer treatment and prices at Lung cancer standard treatment low price Zdenko Kos Foundation

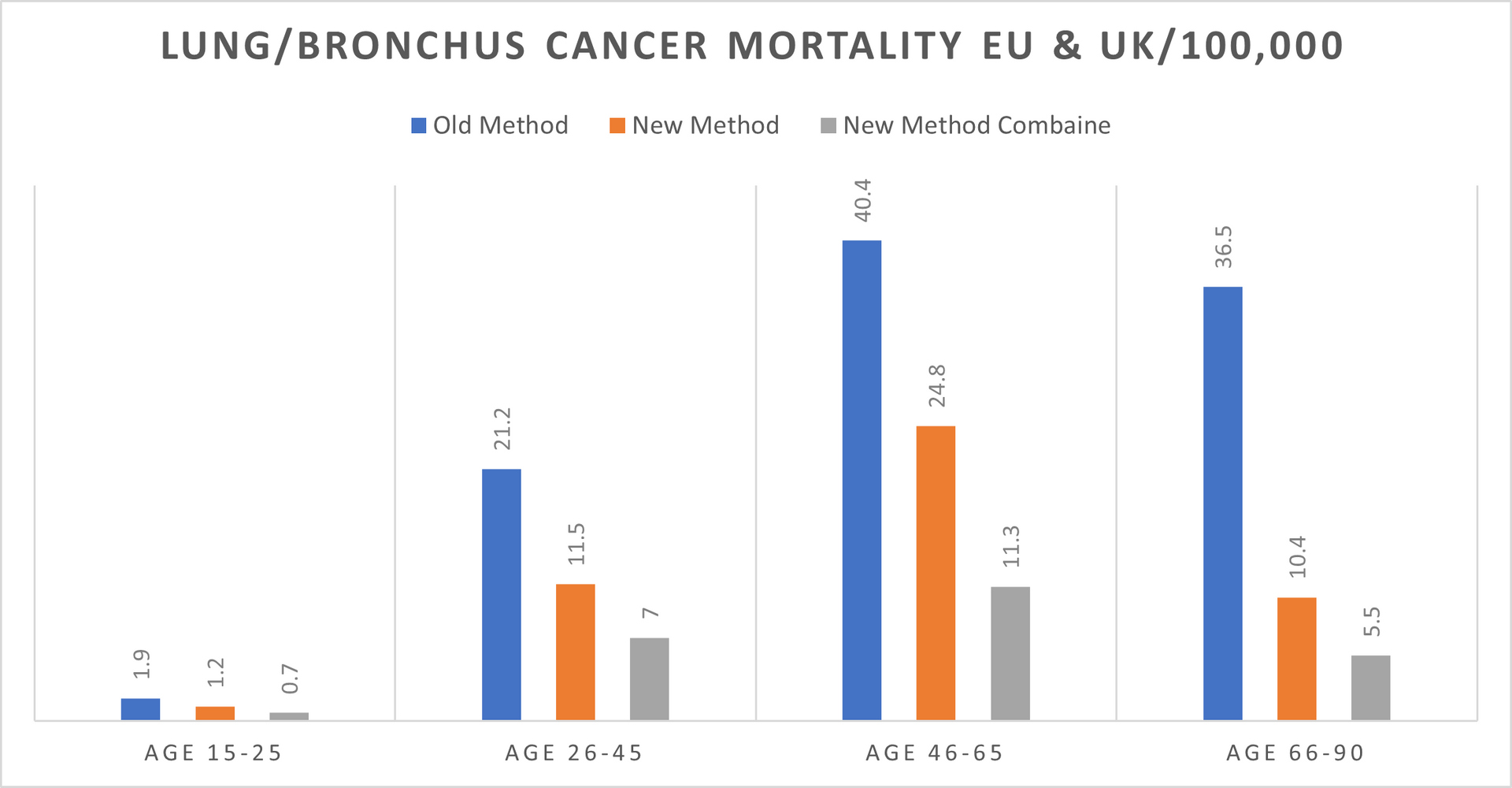

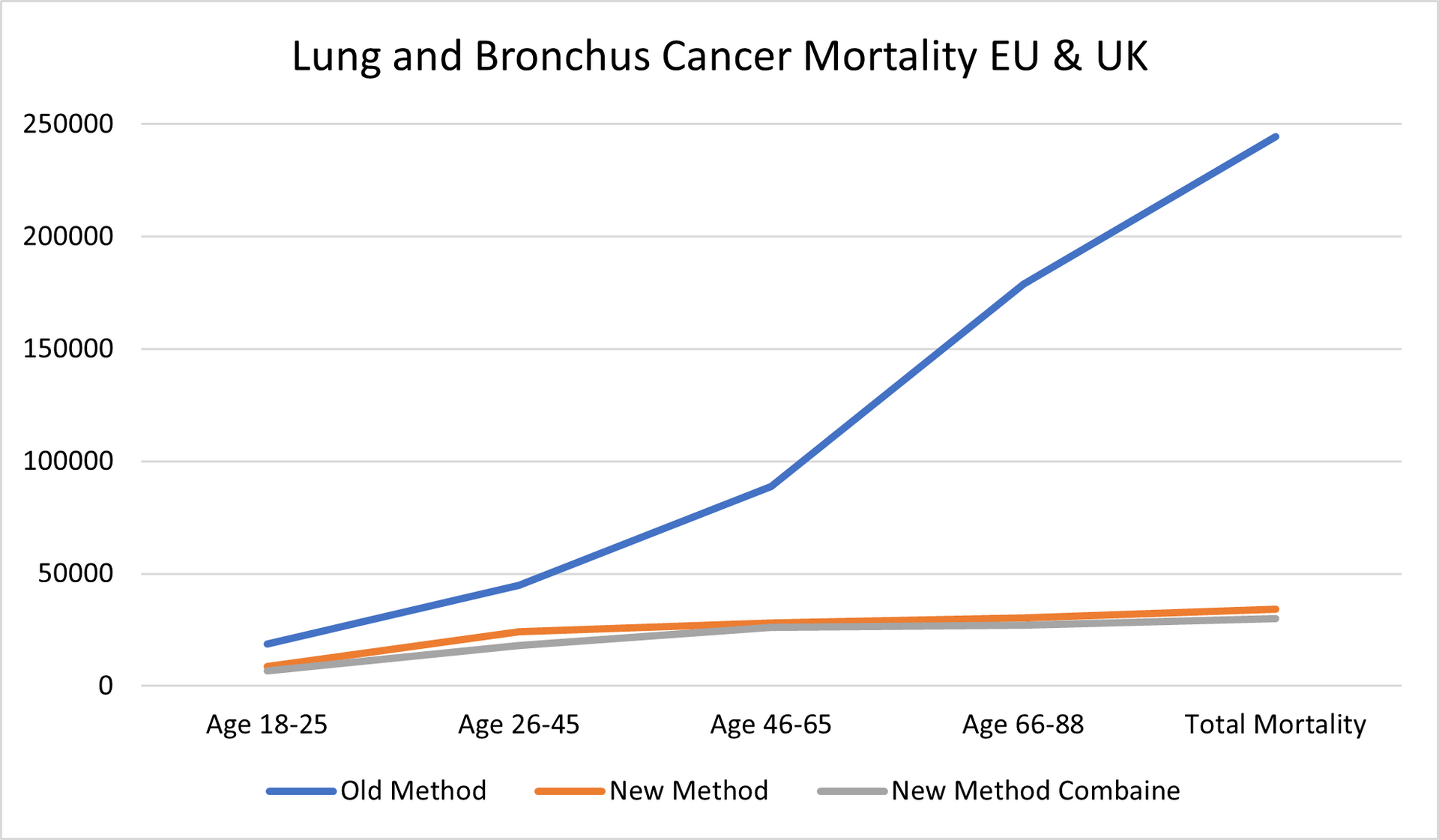

LUNG and BRONCHUS CANCER DATA Period 2019 -2024

Hospital Trials and Treatment with our NEW Medication

Mortality in EU 2019-2024: 288,620; (EU hospitals Standard Treatment)

Mortality in the UK 2019-2024: 91,732 (UK hospitals Standard Treatments)

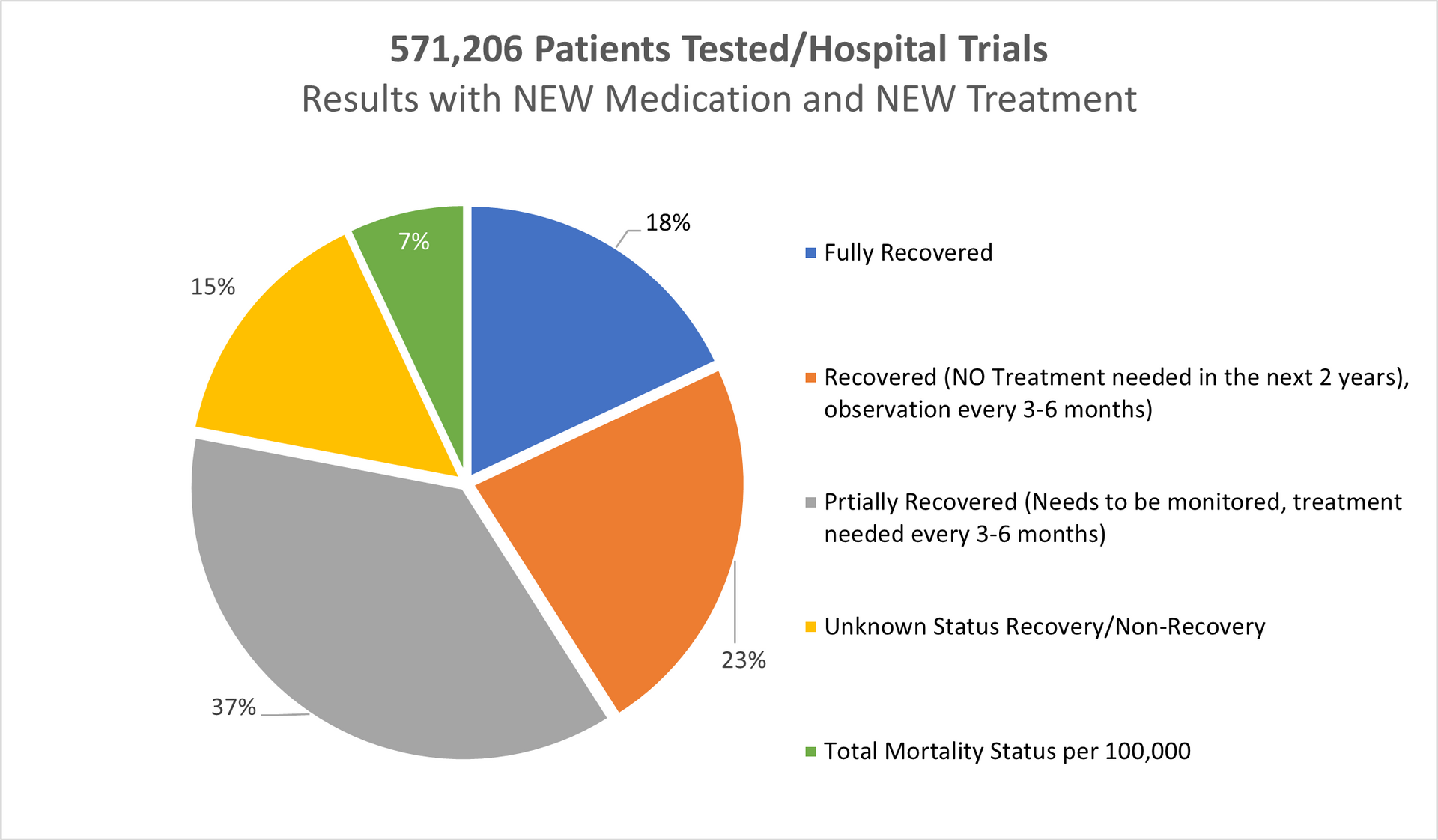

Result using our New Medication/Treatment (Testing period 2019-2024 all age groups):

Tested patients in UK, Switzerland, Germany and Italy: 571,206

Fully recovered: 18%

Recovered (No treatments needed in the next 2 years monitoring every 6 months): 23%

Partially Recovered (Further treatments needed as precaution after 3-6months passed): 37%

Unknown Recovery/ Non-recovery: 15%

Deaths in Total: Less than 7% (The highest % in the group 46-65).

REFERENCES TO THE DATA ABOVE (Period 2019-2024):

Age Gap: The youngest person was not even 8 years of age

The oldest person was nearly 90 years of age

Gender:

Female: 331,003 of 571,206

Male: 240,203 of 571,206

Age group 16-25 > 1.1%

Age group 26-45 > 27.8%

Age group 46-65 > 42.2%

Age group 66-90 > 28.9%

---------------------------------

Total: 100%

====================

Methods:

Old Methods meaning the STANDARD METHODS used by the hospital on a daily basis for the last minimum 5 years in Europe and in the United Kingdom.

New Methods meaning our NEW MEDICATION/TREATMENT with which we came out after over 14 years of research and tests.

New Methods Combine meaning our NEW MEDICATION/TREATMENT COMBINED in double parallel treatment > NEW MEDICATION and different way of treatment combined with chemotherapy or combined with radiotherapy or combined with chemo and radiotherapy.

Separately we tested our NEW MEDICATION combined with "OLD" methods used by the hospitals in Europe and in the United Kingdom however, the final readings cannot be 100 percent accurate and cannot be as such used for whatever comparison.

Mortality:

In the Europe 2019-2024 > 26.1%

In the United Kingdom 2019-2024 > 15.6%

With our NEW Medication/Treatment in Europe & United Kingdom 2019-2024 > Just below 7%.

The % of "Unknown Recovery / Non-Recovery" dropped again (2018/23 was 18%) to 15% mainly in the age group 26-45 which we believe has not increased due to smoking habit still present.

There is an increase of mortality in Europe for 5.9% while in the UK mortality went up by 2.7%.

All patients being chosen randomly what also might be the point of just below 7% mortality rate.

OUR RESEARCH and MORTALITY DATABASE 2019-2024

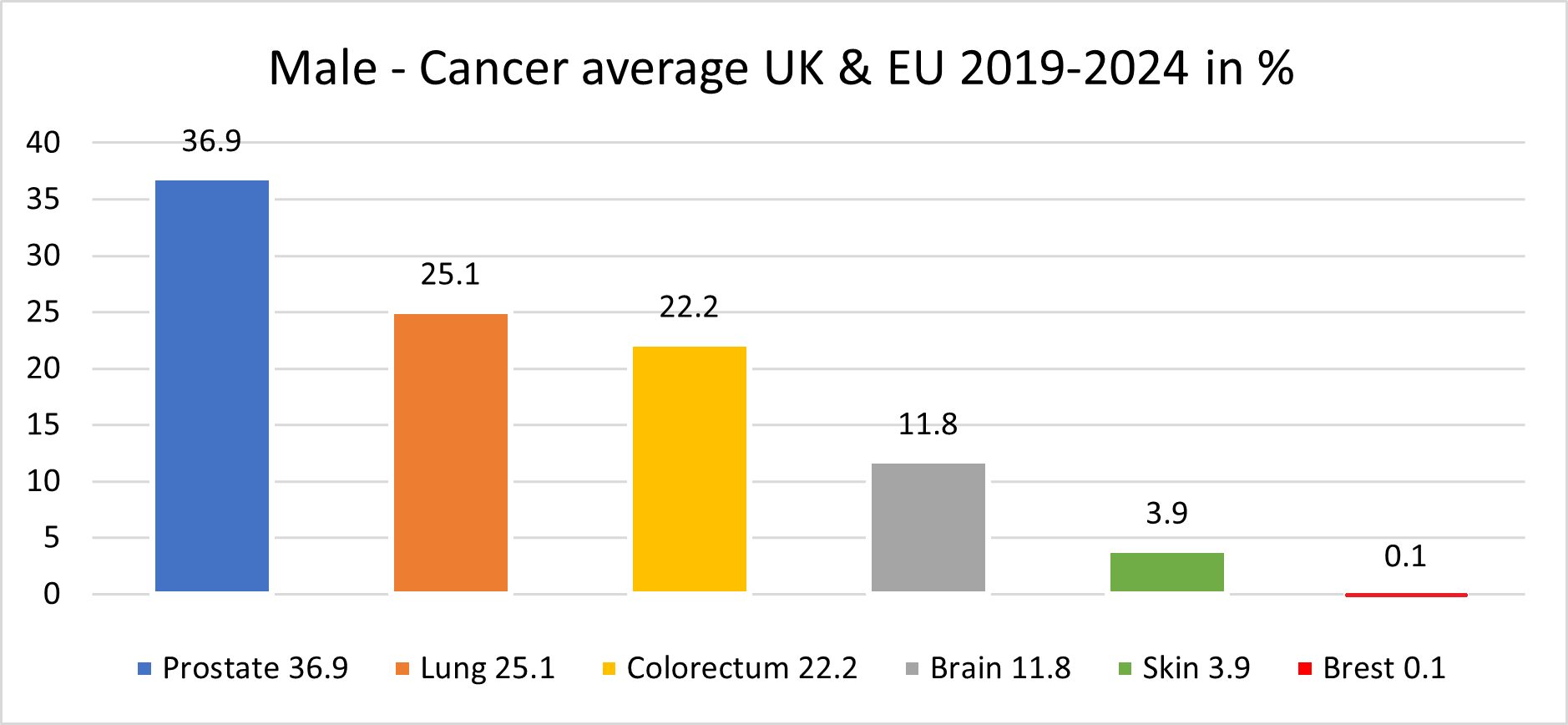

Cancer is one of the biggest health challenges worldwide. Since starting the research in 2011/12, the percentage of all deaths from cancer has risen from 9.6% in 2011 to 14.9% 10 years later; in the last 5 years this has risen again to where we now have 16.2% of all deaths recorded as cancer deaths.

Taking into consideration that in the period 2019-2024 the average European and the United Kingdom population was 760.3 million, an average 4,880,664 new cases were reported yearly during the same period. This is an ASR of 280, and a cumulative risk of 29.8%.

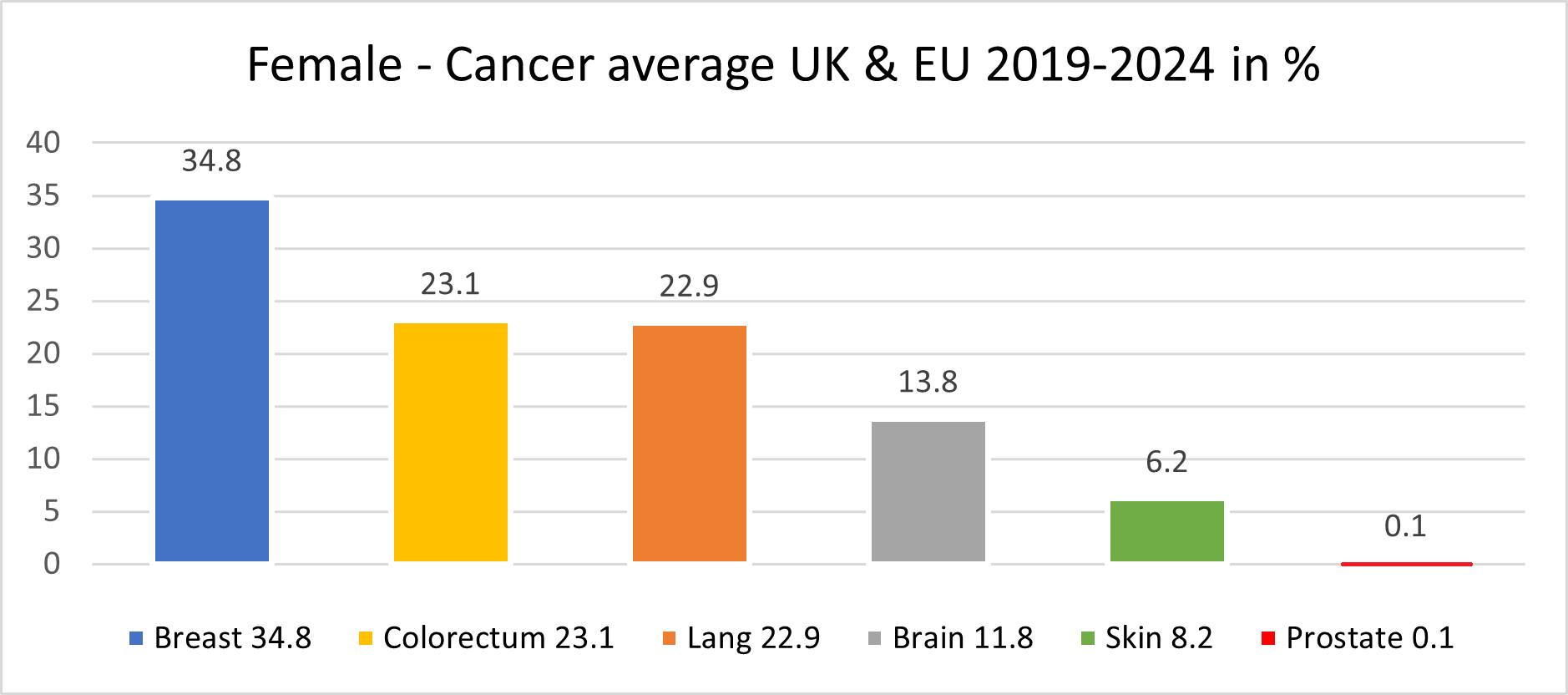

Breast, Colorectum, and Lung cancers were the most common cancers across both sexes.

The male population in this period, some 370.2 million, recorded an average of 2,482,117 new cancer cases per year; an ASR of 321.4 per 100,000 and a cumulative risk of 33.1%.

The top 3 most common cancers among males were Prostate, Lung, and Colorectum cancer.

The female population in this period, some 390.1 million, recorded an average 2,398,547 new cancer cases per year; an ASR of 258.6 and a cumulative risk of 26.5%.

The top 3 most common cancers in females were Breast, Colorectum, and Lung cancer.

A significant point with cancer in the female population was the drop in lung cancer to 3rd place, with colorectum cancer overtaking the 2nd place.

Our mortality database is a collection of death registration data which includes cause of death information from member states; we use only the data which has been properly coded to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD).

What has also changed in recent years is the age of the death rate. This had declined over time in several countries due to life improvements, early diagnoses, medical advances, and a general reduction in risk factors like smoking and even drinking. However, there is a worrying emerging trend with rates of cancer in the population group aged up to 16.

This is rising well over expectations, especially in the United Kingdom, Spain and France.

PERIOD 2018 -2023

LUNG and BRONCHUS CANCER DATA

Lung and Bronchus Cancer Data

Mortality in EU 2018-2023: 244,428; Mortality in UK 2018-2023: 78,823 (EU & UK Standard Treatments)

Result by Starting using our New medication (Testing period 2018-2023 all age groups):

Tested patients in UK, Switzerland, Germany and Italy: 489,727

Fully Recovered: 18%

Recovered (No further treatments needed for period of next couple of years): 21%

Partially Recovered (Further treatments needed as precaution after 6months passed): 35%

Unknown Recovery/ Non-recovery: 19%

Deaths in Total: 7% (Mostly people age 60+).

REFERENCES TO THE DATA ABOVE:

Age Gap:

The youngest person was of 18 years of age

The oldest person was well over 88 years of age

Gender:

Female: 282,036 of 489,727

Male: 207,691 of 489,727

- % of age group 18-25 was 1.2%

- % of age group 26-45 was 24.8%

- % of age group 46-65 was 46.3%

- % of age group 66-88 was 27.7%

Methods:

Old Methods meaning the standard methods used by hospital on daily basis for last minimum 5 years in EU and in the UK.

New Methods meaning our medication/treatment with which we came out after over 12 years of research and test.

New Methods combine meaning our medication/treatment combined in double parallel treatment > new medication and different way of treatment

Separate there are also results of our new medication/treatment combined with "old" methods however the final readings cannot be 100 percent accurate and cannot be as such used for whatever compares.

Mortality:

In the Europe 2018-2023 > 16.6%

In the United Kingdom 2018-2023 > 10.6%

With our medication/treatment in Europe & United Kingdom 2018-2023 > 7.3%.

The % of "Unknown Recovery / Non-Recovery" increase to 19% (2017/22 > 15%).

There is increase of mortality in Europe for 3.1% while in UK mortality gone up by 1.8%.

All patients being chosen randomly.